Is the Pandemic ‘fuelling’ emotional abuse?

- Published: December 12, 2020

- Category: Awareness and Prevention

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

As a nation, we haven’t experienced a pandemic of this scale before; and the impact it’s having on households, families’ finances, routines, living arrangements, and mental health is unprecedented – and significant.

While these factors don’t ‘cause’ domestic or family violence by themselves, they can act as ‘fuel’ – increasing the likelihood, frequency, and even severity of family violence.

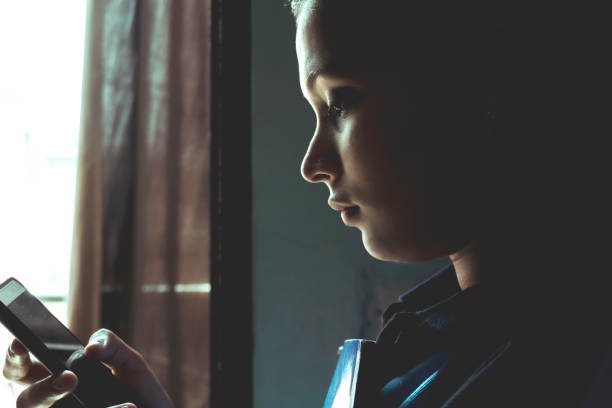

Under lockdown/home quarantine, some people will find themselves at home with an abusive partner without access to their usual support networks. Perpetrators of domestic or family violence may do things like criticise their parents more, increasingly monitor communication devices of children/young adult family members, withhold access to necessary items and use the situation as an excuse to control the family finances.

It is very important to understand the implications of emotional abuse. Perpetrators may use COVID-19 to justify any abusive or violent behaviour, and it works the other way, too: people experiencing the abuse may dismiss or downplay it during the pandemic, using statements like “they’re just stressed”. Over time, the shock factor can also wear off and people end up normalising and accepting domestic violence and abuse.

As a society, we prioritise physical health over mental well-being, despite the very fact that they’re inextricably linked. The violation of our physical boundaries (sexual abuse, physical abuse) is taken into account and considered more problematic than the violation of our emotions. The scars of verbal abuse and emotional abuse are very real and run deep but since they’re intangible, there are not any strict deterrents against the abusers who emotionally/mentally abuse.

Many children, women and gender minorities are on the receiving end of verbal abuse on a daily basis, which is detrimental to their mental health. Unfortunately, verbal and emotional abuse is usually undermined, even by the person experiencing it.

In India, the data provided by the National Commission of Women (NCW) in mid-April suggested that there’s an almost 100% increase in violence and abuse during the lockdown. The other contributory factors regarding the uprising issue of the abuse is stress and associated risk factors such as unemployment, frustration, reduced income, limited resources, alcohol abuse, and limited social support are likely to be further compounded.

The phrases and speech patterns used by their abusers — insults such as “lazy” and “stupid,” statements (“That never happened” or “I never did that”) meant to distort past events, and accusations that slowly isolate the survivors from family and friends — were strikingly similar. As opposed to a bad-tempered partner or someone who occasionally says something cruel and then apologizes, verbal and emotional abusers engage in abuse over years and decades, convincing the survivor she’s at fault and finding ways to cut off her emotional or financial support.

The Office on Women’s Health, part of the Department of Health and Human Services of United States, lists 11 signs of emotional, or nonphysical, abuse, including humiliating victims, monitoring what they are doing, discouraging them from seeing friends or relatives, constantly accusing them of cheating, and telling them what to eat or wear. “Name-calling” and “constant criticism” has been added to that list later. Taking the advantage of the unpredictability of the pandemic, trapping a victim in her home, blaming her for the abuse, damaging objects, threatening to hurt loved ones or pets, and “gaslighting” (distorting the victim’s reality by, for example, denying past events or saying the abuse is “all in your head”) has been increasingly prevalent.

None of these actions involve physical abuse, but they can be severely harmful. The Office on Women’s Health notes, “Attempts to scare, isolate, or control you also are abuse. They can affect your physical and emotional well-being. And they often are a sign that physical abuse will follow.”The potential for it to become physical is often there, but it doesn’t always happen. Separating victims and their abusers is a very important step for ensuring victims’ well-being.

With the pandemic, uncertainty is looming large, which can be an advantage to most abusers, and one of the best ways to deal with this is to make help more swift, and prompt.

What is most important is to reach out as soon as possible. You can reach out to legal authorities that use legal policies for women and child rights protection. Lawyers Collective Women’s Rights Initiative LC WRI runs a pro-bono legal aid cell for domestic violence cases. Human Rights Law Network runs Madhyam Helpline and provides Legal Services. Child Line- is a 24-hour, FREE, nation-wide phone outreach emergency helpline for children in need of care and protection. You can reach out to NGOs like Arpan, Rahi Foundation, Heal, and Protsahan India Foundation, who specifically deal with giving help to abused women and children. You can reach out to the following support circles and helplines:

Shakti Shalini – women’s shelter-(011) 24373736/ 24373737

Saheli – a women’s organisation-(011) 24616485 (Saturdays

All India Women’s Conference-10921/ (011) 23389680

Central Social Welfare Board -Police Helpline-1091/ 1291, (011) 23317004

Counselling Services on Women in Distress – Organised by Delhi Police-3317004

National Commission for Women (NCW)- 7217735372

This article and the attached creative has been created by the MISSING LINK TRUST. To know more about the work we do please check out our website.

Have a look at our social media platforms:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/missingpublicart

Instagram: https://instagram.com/missingirls?igshid=1th1nbat56qfb

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MISSINGIRLS?s=20

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/missingpublicart/

Like what you read? Recommend or share it ahead.

https://kmchistory.blogspot.com/2020/09/pandemic-and-patriarchy.html?m=1

Trafficking And Its Economic Costs – To The Society, The State And The Individual

Addressing The Mental Health Concerns Of Adolescents Within The Anti-trafficking Space